waking up in silence

The perfect image of childhood is a safe metaphysical space where we explore the world and our place in it. War radically deconstructs it. Forced migration expands the world, where new rules, restrictions, and opportunities emerge. But a risk of getting lost between them dwells besides. The directors delicately film how a torn childhood is stitched together in a new context. The observation resembles an appliqué: the former German barracks are the background for the attached figures of children. They are engaged in the usual activities: talking, riding bicycles, throwing berry seeds, whose will reach further? Finally, they learn a new language. And they call their parents: they stay where the war is. This is where the appliqué breaks, allowing painful reality to seep through it.

Mila Zhluktenko, Daniel Asadi Faezi, directors, "Our film was an opportunity to see the consequences of the war abroad, in Germany. We wanted to show how Ukrainians felt after arriving and how German society behaved in this situation. During the filming process, it was important to interact with people sensitively and empathetically to avoid re-traumatisation. Moreover, we did not want to be an additional burden for those who live together in a tiny space and are stressed enough even without people with cameras. So we decided to film outside with the Ukrainian children during their summer holidays. In this way, we became useful to them as a kind of leisure workshop.

Our protagonists live in barracks constructed by the Wehrmacht in the 1930s. The architecture still keeps the traces of previous wars. We were particularly interested in the connection between the past of these barracks and the war experience of the newly arrived residents. This is not the film's primary focus, but still, we wanted to emphasise that, in some ways, history is repeating itself in this place."

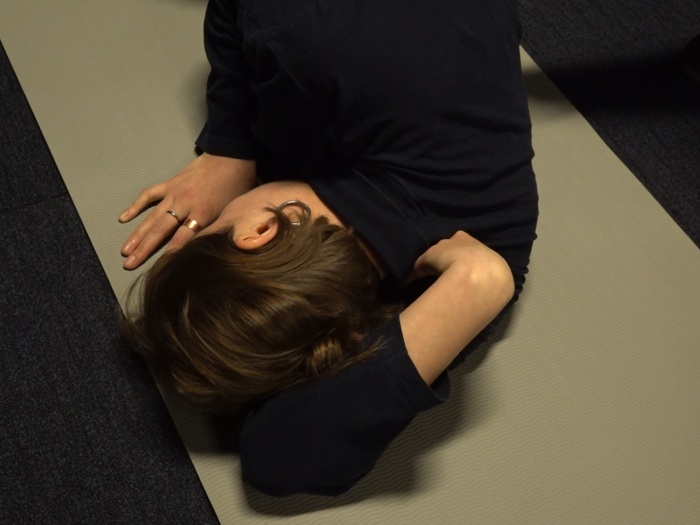

a still from the film waking up in silence

Forest, Forest

We have something in common with the trees in the forest: rootedness and attachment to the place where memories and their material carriers live. Our minds are full of childhood flashbacks in which we see ourselves as imaginary, not real. Instead, we see the world clearly and speak about it honestly because adult problems do not cloud children's optics. The film is based on home footage belonging to one family. Through the immediate, unpretentious lens of a VHS camera, we calmly contemplate how children grow up. The concept of home video implies that every movement is worth capturing. Every movement can be art. I wonder if anyone films forest trees growing up with the same awe?

Maria Stoianova, director, "My work on this montage film took place in two stages: before and after the full-scale invasion. "Before", I was at a residency at Lviv Centre for Urban History and watched a home video in the archive. At that time, I made several montage sketches including various materials. But it was "after" when I chose one of them for work on the film, realising the vague feeling I had earlier when I was watching videos of a family I didn't know. I understood what the film revolves around. This was the answer to the riddle I had asked myself. Seeing the commonality and depth of society's ties in the fragmented private experiences is like seeing the forest behind the trees.

Working with other people's private experiences in the film makes them not strangers to me. But not friends either. It's interesting that indirect experience ends up at a new distance. Paradoxically, this distance creates a special intimacy. It is important to me. The distance to another time, to the protagonists, gets even greater when working with the archives. But the archival footage in the film can also speak to us and tell about us today. Among other things, it is also therapeutic in its own way."

A still from the film Ptitsa

Ptitsa

When a story unfolds in a confined space, the latter becomes a real character. Its attributes force the events and shape an atmosphere that seeps into the interaction and inner state of the characters. The story of this film is calm, even phlegmatic. In the physical realm, everything is in its place, but beyond it lives a sense of dissonance. The protagonists, mother and daughter, are used to each other, but we understand that something is wrong between them. They are tied together, but at the same time, they exist separately. On a structural level, the film includes many visual anaphors. They emphasise the monotony and repetitiveness of everyday life. One needs to listen to the film carefully: its power is in its language. The tranquillity of its image aims to ensure that nothing distracts from the language.

Alina Maksymenko, director, "My camera finally opened up to me. We began to develop a certain linguistic relationship, something more than skills and certain techniques. I realised that the lens has its own way of observing, its own locks to reality. I probably won't be able to list all my findings, but I know what guides me, what feeling is true when I'm filming.

A still from the film Are You Here?

Are You Here?

From the very beginning, we find ourselves in a fragile space between two parallels. Later, we merge with the bitter sadness of the protagonist. The film plot consists of stories, we see one of them but can only hear the other one. Both revolve around the experience of war but in different contexts. One of them is about direct involvement, "here and now". The other is about the distance that makes everything seem monstrous and uncontrollable. By filming the girl's state of mind in migration, the director reflects on what it means to live through a war that is going on in your home country but at a great distance. What does it feel like when peaceful life fades into the background? You are present in it only physically. But in your gut, you exist between two parallels, unable to reach either one.

Zlata Veresniak, director, "I realised that sometimes we, as directors, can be emotionally unprepared to live through the trauma of our characters. Sometimes I didn't understand how to adapt to my protagonist without re-traumatising her. I learned from them that it is important to be sincere with the character in your intentions. In the future, I want to be more open with them.

This project is a bit therapeutic and autobiographical for me. Because, like my protagonist, I don't live with my family, they stayed in Ukraine. Like the protagonist, I tried to convince them to leave. But, unfortunately, this is about the decisions of other adults. While working on the film, I began to understand my family's choice deeper, and why they stayed. We are still close to this day, and she also started understanding better why her family made this decision. We both came closer to understanding why we feel so guilty for being away from our families. So it was also therapeutic for the protagonist in a way."

A still from the film Second Wind

Second Wind

When you balance life and death, and at the last moment, by a lucky chance, life pulls you into its space, you look for signs and instructions for further action. This story is about the film's protagonist. The trauma pushed the man to rethink himself in a new, war context. Many residents of his native city of Chernihiv needed help, so volunteering appeared in his life in addition to music and tea ceremonies. The plot fragmentarily depicts his everyday life, which is full of selfless goodness and the light it brings, and at the same time, is full of pain, suppressed emotions, and destruction, both external and deep, internal.

Maksym Lukashov, director, "In April 2022, Chernihiv was half alive, half destroyed, half empty, half de-energised. I had spent half my life there, and it was painful to see the wreckage of my favourite cinema theatre, the old library and the stadium. It was also hard to see the bombed-out maternity hospital and the ruins of the burnt-out house where my five-year-old son was hiding during the shelling. Amid this horror, we met people strong in spirits. Everyone was holding on as best they could and helping others to survive. What exactly helped them to endure everything and not lose their minds? I think it was the spontaneous mutual assistance. Under the pressure of danger, people rallied together and withstood the test.

Other people's experience becomes my material for creativity. When people tell me about the horrors they have witnessed, my mind is focused, and I try to behave in a way that makes the process productive. It's important to control emotions and not take things too personally so they don't affect the outcome. Sometimes I feel that I am provoking people to go through a difficult experience again. It seems like I'm doing them harm. But then I see that they gain a certain liberation by recounting their painful experiences. For war victims, filming gives them a sense that their experiences and feelings are important to society. That's why I feel emotionally fulfilled afterwards because we are doing the right thing."

A still from the film Mariupol. A Hundred Nights

Mariupol. A Hundred Nights

It is still difficult to talk about Mariupol in a straightforward way. It seems that we are not yet ready to pronounce it or to embrace it. But it is impossible to remain silent either. We have to look for the most appropriate forms that would not dilute the tragic meanings deeply embedded in them. Animation is one of these forms. It is centred around the author's sensual, sentimental optics and allows us to narrow the global collective tragedy to a very personal narrative. Of course, it hurts no less. The soundtrack is a musical adaptation of Vasyl Stus's poetry, and his words are still relevant: they are a reminder of the bitter cyclical nature of our history.

Sofiia Melnyk, director, "I had an inner need to make something about the war. But when you work with documentary material, when you process it, and transform it into a product, you seem to become emotionally numb. In the first months of the war, these photos and stories made me feel nauseous. But now I'm used to it, and it's scary. The war definitely affects the dilemma of the importance of content and form. Because, in this case, the content was definitely in the first place. The problem was rather how to avoid making the form too aesthetic and aestheticization of the war.

The initial desired reaction to the cartoon was donations. I planned to make the access to the film public to allow as many people as possible to see it. So my dream reaction was that they would watch it, understand our situation and make a donation. But some festivals became interested in our work, so we decided why not? The festival is an opportunity to talk about the war, about how we can and should help. I also wanted to show that war is not something ambiguous or ambivalent. It's an absolutely unambiguous situation: there is an attacker, and there is a victim – people who are defending themselves."

A still from the film One Aloe, One Ficus, One Avocado and Six Dracaenas

One Aloe, One Ficus, One Avocado and Six Dracaenas

When people leave or lose their homes, they often say, "The most important thing is that we are alive". However, this statement is questionable. On the one hand, life is indeed the highest value. But home, its materiality and objecthood in each individual case, is about powerful emotional attachment and, finally, about well-being. In the film, the heroine tells her own story through the prism of the things she has lost. Listening to the voiceover, we observe Ukrainian refugees in a warehouse sorting through the things they have received from their homeland. Neglecting material things is a great privilege for those who choose it.

Marta Smerechynska, director, "I made the film while being far away from home with an international team. Therefore, the first challenge was to put into words and convey to each of the film crew members an experience Ukrainians live with. An experience I considered important to give shape to. During the work, I faced unexpected unpacking of dimmed and blocked emotions and reactions. A re-awareness of what has been lived. I realised how much I had to process. But the most important thing is a sense of responsibility. After all, the war is still going on. For everyone who sees this film, it provides knowledge about our experience and can influence people's actions from the desire to donate to the willingness to hear and support temporarily displaced Ukrainians.

For me, these eight minutes are a letter of farewell to the old us, who we were before the full-scale invasion. It is an opportunity to remember, show respect and say goodbye to home, the way it was "before". And to define for ourselves what "home" is now. Therefore, I advise the audience to be open to personal memories and what they require: a hug, pity, or to letting them go."

A still from the film The Mist

The Mist

A real pain moves like a kaleidoscope in front of us. It may seem that when it has acquired such material forms, it becomes easier to comprehend and reflect on, but it is not. It is okay not to know how to explain to yourself what happened in the Kyiv region and how to sublimate this experience. Perhaps, this is one of the reasons why we make films: to talk about these topics with ourselves and others. Through the language of cinema because ordinary words show unprecedented powerlessness. The film documents Russian war crimes in Kyiv region. When fleeing, the Russians left behind traces of death, through which - and in spite of which - life is making its way.

I don't expect anything from the audience, I don't plan to control their attention. I think that cinema is already a rather authoritarian genre in terms of controlling accents. And the theme of everyday life implies a wandering gaze. Perhaps the only thing I hope for is a vague sense of recognition. But what kind of recognition it is, the viewers can only decide for themselves. When I think about all of us, I think about the state of disorientation that seems to have been prevalent for most at the beginning of the invasion. And the sense of loss that unites us."

A still from the film Chornobyl 22

Chornobyl 22

In March 2022, the news about the occupation of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant caused justifiable alarm. In our collective consciousness, the Chornobyl myth is on par with myths about the end of the world, but it only concerns a narrower territorial coverage. Looking back at history, this can be logically explained. More than a year later, we have the opportunity to hear firsthand what happened at the occupied station. The unknown was disturbing, and the known causes rage and bitterness. But at the same time, I deeply respect people who, risking their lives, did everything possible to bring the Ukrainian victory closer.

Oleksiy Radynski, director, "We were not just making a documentary, but also collecting evidence of Russian war crimes for international criminal courts. During the research interviews with witnesses of these crimes, the most difficult thing was to find the right balance between a cinematic interview and the collection of facts that would become the evidence base in court.

I am interested in any reaction from the audience. I cannot expect anything in advance, let alone impose my opinion on them. But I would pay attention to the first few seconds of the film: it is worth watching carefully from the very beginning."

A still from the film I Stumble Every Time I Hear From Kyiv

I Stumble Every Time I Hear From Kyiv

The film's title perfectly explains the chosen format. Every time contacting with the space of Kyiv (which is only possible online), the director feels that she is running out of words. Therefore, through cinema, she gives power to the words of her friend who stays in Ukraine during the war. This form is true for many Ukrainians who want and deserve to be heard. It is not only a matter of psychological release but also of survival. The friend shows flowering trees, her favourite buildings, and her room illuminated by the sun. All these poetic details of everyday life during the war become indescribably fragile and, therefore, so valuable. An air raid siren interrupts the birds' singing making this fragility even more noticeable.

Daryna Mamaisur, director, "I often noticed when my voice didn't seem strong enough or convincing enough to be heard. I have always been interested in the situation of the vulnerability of language or our vulnerability in it. The war only intensified this feeling. At that time, words seemed powerless in an attempt to grasp reality. So I came up with the idea to work with the voice and record voice training classes, which, to my surprise, partly resembled a therapy session. It was also a question of whether I had the right to speak about the experience of war, which I knew only from a distance. Finally, my speech in the film ends up being a stutter, only an attempt. Instead, a lot of time is devoted to the stories of my friend Tania, who was in Kyiv at the time.

It was also important for me to talk about the banality of the war experience, about people's desire to return to normalcy, which, although distorted, carries a thirst for joy and attention to everyday things. For me personally, this film was, among other things, an attempt to cling to 'normality', to attend classes, to make efforts and work, not only to get bogged down in the news but also to try to capture our experience of that turbulent spring through cinema."

Main photo: a stll from the film Forest, Forest.