This year, the Docudays UA festival celebrates its 20th anniversary. We brought together the people who stood at its origins: Gennadiy Kofman, Volodymyr Yavorsky, Alla Tiutiunnyk, and Roman Romanov, and asked them about the first steps of the festival, problems, achievements, and challenges for documentary filmmaking in times of war.

Tell us about the festival's origins. Under what circumstances was it conceived, and what preceded its appearance?

Gennadiy Kofman:

The cinematic landscape of Ukraine at that time consisted of a few films that were produced in the country every year. The Days of National Cinemas in Kyiv and in 2-3 other cities of the country felt like national holidays for cinephiles. With the speed of the Internet connection, it sometimes took more than five minutes to load a simple email. We haven't even heard of pirated content yet!

So when one of my films took part in the One World Human Rights Documentary Film Festival in Prague, I discovered a fantastic layer of a hitherto unknown form of cinema – human rights documentaries. In the early 2000s, Ukrainian audiences had no idea about it, let alone the possibility to watch author's documentaries in a cinema or on TV.

Ever since then, I’ve dreamt of bringing the best contemporary world documentaries to Ukraine. And watching them using my official position (smiles). To be serious, from the very beginning, we decided that the festival should introduce the best documentary films to the audience not only in Kyiv, but in all parts of the country.

And how did this dream come closer to becoming a reality?

It turned out that I was not the only one who dreamed of a similar festival in our country: I met Volodymyr Yavorskyi, who soon became the executive director of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union. Although Volodymyr and I sometimes had radically different views on the development of the festival, the Helsinki Union is a co-founder and one of the festival's reliable partners.

photo from the opening of Docudays UA-2017, report.to

Volodymyr Yavorskyi:

For the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, it was primarily a way to reach an external audience. We were interested in informing people about human rights. Human rights defenders are rather boring people, and it is difficult for them to convey complex legal concepts to the general public. It is hard to relate some of the reports, monitoring results, or court cases in accessible language, especially to young people. We viewed documentary screenings as a bridge through which ideas can be conveyed to society. Documentary films prominently demonstrate the issues that we try to describe in legal language, so we saw a prospect in both screenings and production of documentaries. Our seemingly different goals – Gennadiy’s creative approach and my human rights issues – have organically merged in our cooperation.

How did you manage to organize the first festival in 2003?

Gennadiy Kofman:

The festival opened in Kharkiv on November 14, 2003, and then traveled to Donetsk, Odesa, Lviv, and Kyiv. The idea was supported by the Kyiv office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and they provided a lot of organizational support. And the first and only donor of the very first festival was the International Renaissance Foundation. Since then, the foundation has become our strategic partner for many years, and Roman Romanov, the director of the Rule of Law Program, has turned into the festival's guardian angel.

Roman Romanov:

I remember that, when I was working on the development of the human rights movement at the International Renaissance Foundation, I wanted to find a uniquely Ukrainian way of bringing art and human rights values together. I had already had contacts with the organizers of the Prague One World festival and the Warsaw Watch Docs: they were all looking for cooperation with Ukraine. During one of the meetings, we found a common interest with the representatives of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in Ukraine, but their interest in the festival was limited to the topic of protecting the refugees’ rights. We agreed to try and develop a common format: an event about human rights with an opening film about the refugees’ rights. And so it happened.

photo from the opening of Docudays UA-2017, report.to

Did you plan the development for the subsequent 20 years? What challenges did you face?

Gennadiy Kofman:

Back then, 20 years ago, it was impossible to imagine that Ukrainian cinema would be represented at all the most prestigious A-category film forums and leading documentary film festivals. Even though from the first day of our work on the festival, we regarded promoting the integration of Ukrainian cinema into the world film process as one of our tasks, it felt like drawing a roadmap to a mirage.

Volodymyr Yavorsky:

The creative search for the format took us some time. There was no consensus among our partners about what kind of films to screen: there were those who believed that the festival program should include both documentaries and fiction films...

Gennadiy Kofman:

This was one of the reasons why I almost left the festival after the first edition in the fall of 2003, but Volodymyr Yavorsky persuaded me to come back and assured me that we would create a documentary film festival. So it happened, and the second festival took place in March 2005. However, one of the main challenges of that time was almost complete absence of Ukrainian documentaries. The 3-5 films we managed to find could not form a full-fledged national program.

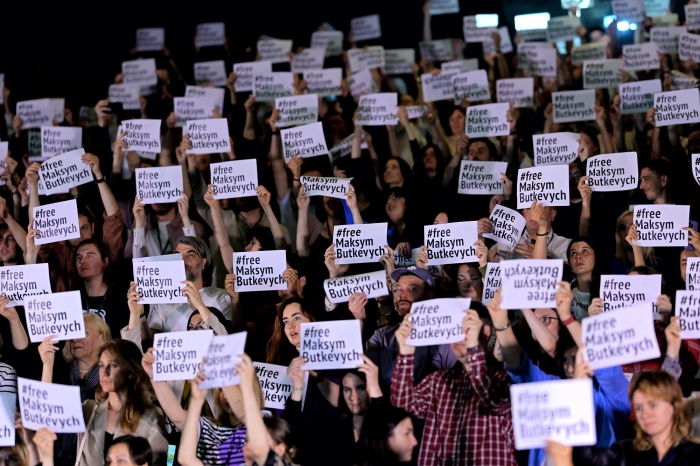

photo from the opening of the 20th Docudays UA, Stas Kartashov

Gennadiy Kofman:

In the early years, the audience had some distrust of the program, and the attitude towards documentary films was dominated by the idea that they were too boring, preachy, and uninteresting. After the first screenings, the opinion changed, and it turned out that it could be even more interesting than fiction. Some of the viewers refused to believe that the characters and events in the films were real and not fictional. I remember how a very special group of young people came to the cinema in one of the cities and became indignant that there was no "normal" movie at that time. We persuaded them to come into the cinema; after the screening, they left with red eyes and thanked us for a long time. We’ve even earned some fans who would be waiting for our programs for the following year and bring their friends and girlfriends to the screenings and discussions. All this inspired us and gave us strength to continue this work.

Alla Tiutiunnyk:

I remember the times when the festival audience at the House of Cinema was scarce, and there was only one competition program and only 2 prizes – from the festival itself and from the Union of Journalists. However, it was a real holiday for documentary filmmakers and a unique opportunity to watch the best films from around the world, and to show their own films.

Roman Romanov:

From a small event that built a bridge of mutual interest between the communities of filmmakers and human rights activists, Docudays UA turned into a nationwide event which appealed to young audience.

photo from the opening of Docudays UA-2019, report.to

Can you recall the most significant stages of the festival's formation?

Volodymyr Yavorsky:

Every year, we would reach a higher level: we brought the best documentaries from all over the world, invited filmmakers, held more workshops, and increased our outreach to the regions. I believe that the turning point was when Andriy Matrosov, a human rights activist from Kherson, became the festival producer. This gave a new impetus to the festival, which started developing rapidly. We had a breakthrough in all respects: in the filmmaking environment, in the human rights community, and in the eyes of the general public. Gradually, the festival grew into the current Docudays UA, which, as I heard from one of my colleagues, has become a "fashionable event." Unfortunately, Andriy Matrosov died in early 2010, and it was a tragedy for everyone.

Alla Tiutiunnyk:

In 2007, Volodymyr Yavorsky offered our team to take part in the preparation of the 5th Ukrainian Context Film Festival (as Docudays UA was called then). That's how I, Svitlana Smal, Roman Bondarchuk, Darya Averchenko, Denys Kostiunin, and Andriy Matrosov, who became its producer, joined the festival.

It was a completely new thing for us, it was a little scary, but we went for it...

We had a fantastic team of young, brave, talented people who dreamed of building a state governed by the rule of law. In the late 90s, we created two human rights NGOs in Kherson: the Charity and Health Foundation and the “Pivden” Journalists Association. We organized seminars on human rights, conducted investigative journalism, defended human rights in courts, taught judges to respect the decisions of the European Court, invited human rights activists and scholars from around the world to international conferences, and made documentaries. By the way, in 2006, our documentary A Beach for an English Lord, directed by Roman Bondarchuk, participated in the festival.

Gennadiy Kofman:

After the Kherson team joined the organizers, the work became more systematic and structured, and its chaotic nature subsided.

photo from the opening of the 20th Docudays UA, Stas Kartashov

What achievements of the festival are you most proud of?

Volodymyr Yavorsky:

There are many of them. The festival played a crucial role in the development of documentary cinema in Ukraine. Nowadays, such films are very prestigious. We have developed a strong school of documentary cinema, a lot of films are being made, and Ukraine is present at virtually all festivals of this genre in the world. We have seen this boom for the last 5 years, even before the full-scale invasion. I believe that the festival played a key role here, because it has mobilized so many spheres – education, production, and the community itself. It has become a phenomenon of cultural life.

I also think it is very important to reach out to people. Usually, NGOs have limited contact with ordinary people, and the festival is attended by more than 100 thousand people every year. Today, it is one of the largest awareness projects in Ukraine. It is not only about screenings, but also an educational event, a discussion that makes people think. In my opinion, it is Docudays UA that has had a serious impact on the formation of Ukrainians' awareness about human rights.

Gennadiy Kofman:

For many years now, the festival, or rather the NGO “Docudays,” has been an institution that covers many crucial areas of the country's cultural and social life. In the pre-lockdown years, the festival traveled to almost 200 villages and cities in all 22 regions of Ukraine, and our 44 partner NGOs constitute a constantly active network of Docudays UA film clubs in libraries, educational institutions, and penitentiary institutions. We have an ambitious industry platform, the DOCU/PRO festival, and the fantastic Human Rights Department. Every year, Docudays UA holds presentations of Ukrainian films at the most influential film festivals and markets for author documentaries, publishes a catalog of Ukrainian documentaries in English, and so on…

Today, the Docudays UA team consists of representatives of several generations, and this guarantees that the festival will not stop developing in the near future. All this turns the festival into a popular event for the younger audiences.

In our country, a completely different civilization of wonderful, bright, free personalities has grown up and formed. In the early years, at many film festivals I attended, I was often the only representative of Ukraine; nowadays, there is an incredible number of Ukrainian documentary filmmakers in various sections, programs, conferences, and project markets of film festivals all over the world. It is delightful to realize that most of the active and prominent young documentary filmmakers in our country grew up and developed along with the festival.

Alla Tiutiunnyk:

The festival emerged at a time when almost no one in Ukraine had seen real documentary films, when 99% of Ukrainians considered popular science TV programs to be "documentaries", and when about 80% of Ukrainians had no idea what human rights are and what to do about them. From the very beginning, it attracted talented, ambitious, daring perfectionists who dreamed of making Docudays UA the best human rights documentary film festival in Europe. Over the years of the team's hard work, it has become true.

I remember March 23, 2013, when a blizzard started on the opening day of the 9th festival in Kyiv. The city was covered with snow, and all public transport, including taxis, stopped. The entire team was worried: would the festival take place or not? Nevertheless, in the evening, snow-covered people flocked to the House of Cinema in droves, and eventually filled all the floors – standing in the lobbies, sitting in the halls and on the floor... It was a moment of happiness, pride and realization: the festival has real fans, and there are many of them!

installation "Outside the Window" (Yevhen Arlov) of the interdisciplinary art program at the 20th Docudays UA, Zhovten Cinema, Stas Kartashov

What are the characteristic features of Docudays UA during the war?

Gennadiy Kofman:

The team immediately responded to the challenges that arose in the first hours of February 24, 2022. This response includes the DOCU/HELP initiative to support Ukrainian documentary filmmakers who tell the world about Russia's crimes in Ukraine, as well as the incredible War Archive project.

Alla Tiutiunnyk:

For some time after February 24, 2022, it seemed to us that people were not interested in film clubs, that they would not want to watch documentaries anytime soon. However, already on March 17, the Film Club on Zelena Street in Chortkiv screened the 2015 Serhiy Lysenkos’s film Khottabych and His Team about the volunteers. By the way, this film is one of the nine parts of the series Encyclopedia of the Maidan, created on the initiative of the NGO Docudays, and we are proud of it.

Today, 477 film clubs are registered in the DOCU/CLUB network: 163 of the "pre-war" ones have resumed their work, 148 have registered after February 24, 2022, and applications for opening of the new ones are coming in every day. During the full-scale war, the existing film clubs held 1476 screenings. Despite the air raid sirens and shellings, people want to gather and watch documentaries, learn how to defend their rights and influence the government, help each other, dream of victory together, and plan the rebuilding of Ukraine. 30 film clubs are currently conducting advocacy campaigns in their communities. This is how civil society is being formed.

Volodymyr Yavorsky:

The festival and its team have been forming for many years, even though its core has been working for a long time. This war is very personal for each and every one of them; there are many personal losses, personal experiences – it's not just an outsider's view. We live everything through our own experience, and we speak on our own behalf. In general, what makes this year's Docudays UA different is that festivals are impossible during the war! It shows the essence of documentary filmmaking: being in the center of the event and reflecting on what is happening. It shows that we are able to work not only in difficult conditions, but also during the war.

What are the challenges facing Ukrainian documentary filmmaking today, and how does Docudays UA respond to them?

Volodymyr Yavorsky:

Documentary cinema has always been challenged by television documentaries: they are now rapidly spreading and multiplying in Ukraine, and television formats are actively supported by the authorities. This boundaries between television and documentary is unclear for many people. Therefore, for the festival, the question is to build this line and keep the quality level high.

We are currently focused on three spheres: developing a community of people engaged in documentary filmmaking and not interested in turning it into a TV show; increasing the professionalism of this community through training; and working with filmmakers to create meanings for their films.

Gennadiy Kofman:

I see two issues for the Ukrainian film community in the near future. The first challenge is to prevent film festivals around the world from abandoning the topic of the war in Ukraine under the pretext of "it’s too much, our audience is tired". The second one is the formation of independent funds to support Ukrainian documentaries.

Main photo: from the opening of the 20th Docudays UA, Stas Kartashov.

Text: Slava Naumova.

_____________

The 20th anniversary of Docudays UA is held with support from the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine, the Embassy of Switzerland in Ukraine, the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation, US Embassy in Ukraine, the Embassy of Ireland in Ukraine, the Embassy of Denmark in Ukraine, the Embassy of Brazil in Ukraine, the Polish Institute in Kyiv and the Czech centre Kyiv. The opinions, conclusions or recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the governments or organisations of these countries. Responsibility for the content of the publication lies exclusively on the authors and editors of the publication.