Travel around the 18th Docudays UA programme. Read about DOCUART selection in a review by a film scholar and director Oleksandr Teliuk.

In her text Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), Susan Sontag noted a paradox that characterizes a photographic image: its machine nature claims to be objective and, at the same time, conceals the motivation behind creating the photo. The films in this year’s DOCU/ART programme lay bare this subjective aspect of an image. Each of them does not just tell its story, but also reveals the personal motivations of its author.

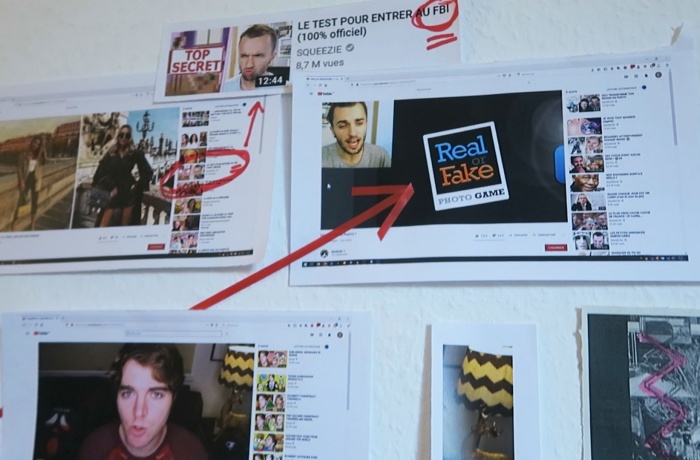

Subjectivity in non-fiction cinema since the early 2010s most often takes the form of the film essay genre. This is the form used by the most expressive films of the programme, the creations of the French researcher and artist Chloé Galibert-Laîné. The festival presents two of her films: Watching The Pain of Others and Forensickness. Both are examples of desktop documentaries and a kind of screen adaptation of critical articles about vernacular production of visual information online.

Watching The Pain of Othersreveals a whole cascade of cultural references. Chloé Galibert-Laîné analyzes The Pain of Others (2018) by Penny Lane, a film built on vlogs by women with the parascientific Morgellons disease and references to Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others.

In a balanced and witty manner, Galibert-Laîné analyzes her experience of watching The Pain of Others. She tries to understand why she was annoyed by the film’s physicality; she studies the structure of the film in an editing app; she watches the filmography and creative themes of Penny Lane; finally, she calls the author of The Pain of Others and writes to its characters in vain.

With her close attention to The Pain of Others, Galibert-Laîné achieves a paradoxical state, albeit a typical one for internet production, when the derivative work of art – a kind of remake – goes further than the original and touches upon more complex topics, such as the connection between conspiracy theories and online activism, virtual manufacturing of empathy, and the narcissism of online (self)representation.

In Forensickness, the filmmaker uses the same method to analyze another film, Watching the Detectives (2018) by Chris Kennedy, dedicated to the amateur online investigation of the Boston Marathon terrorist attack of 2013, conducted by Reddit and 4chan users.

The author conducts her own control investigation: looks at other works by Kennedy; deconstructs the detective film genre; contemplates why visual materials look more convincing in the analogue form. However, her interest (even more than in Kennedy’s case) is not in the fact of the terrorist attack itself, but rather in the way visual data from open sources generate desire among users to imagine themselves as Detective Columbos.

In Forensickness, Chloé Galibert-Laîné labels Kennedy’s film as ‘critical cinema,’ but this definition would fit her own creations. In addition to the academic style, the developments of guerilla online journalism in the Bellingcat style, what’s original about her films is also the use of semantic similarity between the Internet interface and film, which is characteristic of video essays. In general, Galibert-Laîné uses the ideas of Sontag and Debord to reveal how consumerism, conspiracy mindset or Hollywood cliches shape the visual landscape of the Internet in the early 2020s.

Two other films in the DOCU/ART programme are made in a more classical vein. The Filmmaker's House by Marc Isaacs also offers a low-budget documentary story made with everyday means. The filmmaker, Marc, receives a call that funding for his upcoming film has been denied. Money, they say, are only given to films about sex and serial killers, which is not his case.

In response, Marc starts to zealously transform the space of his house into cinema, aiming his subjective camera at home ‘actors’: his housekeeper, builders, his neighbor, etc. A separate theme in the film is the hospitality of the filmmaker, who also invites a homeless man’s ‘film’ into his house.

However, while some other similar claustrophobic or home movies (a classical example is This Is Not a Film (2011) by Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb) often had a political subtext, the situation in The Filmmaker’s House is rather opposite. Because instead of an innocent sharp humorous story aimed against the narrow tastes of the contemporary festival film institutions, the screen shows a petty neocolonial self-portrait without a face: a story about the difficulties in the life of an independent male artist.

The British man, deprived of a grant, incessantly films his Colombian housekeeper, a homeless Slovak man and his Pakistani neighbor. And although the “good host” Marc, of course, strives to see the humanity of his characters, the film still seemingly lacks the realization that the times of the romantic depiction of hardship a la Dickens have long passed. However, the ethical question of whether the filmmaker realizes the incorrect configuration of power in the film or, on the contrary, constructs it as a covert self-ironic subversion remains open.

Another film in the programme, The Last Archer, takes the form of a long-overdue conversation with one’s family. After 23 years of living in Madrid, the filmmaker Dácil Manrique De Lara Millares returns to her childhood home in the provincial Las Palmas to tell the story of her grandfather, the artist Alberto Manrique, who has passed away.

Using her personal memories and conversations with her grandmother, the filmmaker uncovers family secrets. The key component in the film is also the generous visualization of memories conveyed by a family photo album, amateur archive footage and elegant southern decor in her old childhood home. Completely new scenes intersperse unique archive films featuring the artist: Dácil started filming her grandfather before his death in 2018.

Moreover, the complex family story emerges in the film as it explores the interesting Spanish art phenomenon of the LADAC group (the Archers of Contemporary Art). Its co-founder, the oil and watercolor painter Alberto Manrique, represented the first postwar generation of Spanish art that turned to the heritage of the Spanish school of surrealism in their striving to invent a new avant-garde style.

However, the film by Manrique the granddaughter does not seek to develop on her grandfather’s avant-garde ambition. Her rather cautious film does not strive for innovation or ambiguity. Despite its candid, sometimes even intimate intonation, the film mostly balances between an encyclopaedia entry and a panegyric based on biographical themes.

The Last Archer also features a reserved subjective theme. Although the filmmaker barely reveals her face, she expresses the melancholy search for the lost time, the compulsory anxiety after the death of a family member, and the private archeology of identity.

Thus, the DOCU/ART programme proposes three documentary methods, each of which, while demonstrating different versions of working with the media of video, the internet and photography, brightly reveals the individual filmmakers’ subjectivities.

Main photo: a still from Forensickness.

Stills from Forensickness, Watching The Pain of Others, The Filmmaker's House.