The documentary period of Krzysztof Kieślowski's work remains lesser-known to the general public than his feature films. By the 80th anniversary of director's birthday,

we will rediscover his documentary films within the retrospective Krzysztof Kieślowski: a documentary biography, curated by the eminent Polish director Agnieszka Holland.

Read more about Krzysztof Kieślowski's documentary films, the characters, the moral dilemmas in filmmaking, and the reasons for shifting from the documentary as a genre and medium in the text by Agnieszka Holland.

For a while, Krzysztof Kieślowski was only known as a documentary filmmaker. This was in the period between his student years at the film school and until the second half of the 1970s. During his studies, documentary filmmaking was the most noble genre for Krzysztof Kieślowski. Undoubtedly, he was influenced by the professor and prominent documentary director Kazimierz Karabasz. After all, Kazimierz Karabasz’s wife, Lidia Zonn, edited most of Kieślowski’s documentaries.

During this creative period, Kieślowski avoided manipulation; and for him, manipulation was a film plot that is too original, a structure that is too visible, the presence of an informative or author’s commentary. Krzysztof was convinced that films should not give opinions either about phenomena or about characters. Life is as it is: you just have to “see” it and look under the surface of the visible.

The political nature of films in this period is obvious: they showed reality without decoration in its poverty, ugliness and often heroic absurdity, but with a kind of special sensitivity. For Krzysztof, it was the usual world, his world. It did not evoke anger or surprise, and Krzysztof did not evaluate it. He picked non-obvious protagonists, ordinary, neither good nor bad, people who did their difficult and unattractive jobs with hard work, obedience, and often with pride.

He formulated the philosophy of his documentaries best in his feature film which was probably the first one noticed in the world, Camera Buff. The protagonist, factory worker Filip Mosz buys an 8mm camera just to document the growth of his newborn daughter. But instead, he becomes a true filmmaker who fights the system for the truth and honesty of his film story – the truth and honesty of an ordinary protagonist and his world.

Kieślowski’s transition to feature film was difficult. He filmed his medium-length debut Pedestrian Subway twice: the first version felt too artificial and unsatisfactory to him. He worked with great actors, but in the frame, they looked fake to him, worse than documentary film characters. Kieślowski didn’t know how to work with them and direct them. In the end, Kieślowski threw all the material out and bought film on the black market for his own money to film everything again overnight, practically in one take (the decision to buy film on his own was caused by the fact that directors were issued a small quantity of film; this policy was a weakness of Polish filmmaking and forced directors to construct films in their heads before shooting).

Kieślowski’s next feature attempts were more successful, but he mostly worked with amateurs. Only the meeting with an extraordinarily open and modern actor Jerzy Stuhr allowed Kieślowski to appreciate the potential of fiction, in which he was gradually achieving greater accuracy and freedom of expression.

Kieślowski’s documentaries can be divided into two main groups: portraits of individual protagonists (The Bricklayer, First Love, Curriculum Vitae, From a Night Porter's Point of View, The Photograph) and of communities and occupations (From the City of Łódź, The Factory, Hospital, Railway Station). Karabasz’s lens was especially important for the films in the second group: a way of seeing and reproducing reality, mood in combination with editing precision. It was Kieślowski who said that by placing a camera in one place and not another, we’re making a moral choice.

He did not evaluate ‘ordinary’ protagonists; and with the same unbiased curiosity, he also watched the ambiguous party figures. At the Documentary Film Studio on Helmska Street[1], Kieślowski was jokingly nicknamed an ‘ornithologist,’ or, more maliciously, a ‘singer of party tears.’

His curiosity and close observation of the mentality and behavior of ordinary party functionaries manifested the most strongly in Curriculum Vitae. The film, after all, was not a pure documentary, it was a dramatization: the lines were written, the protagonist was played by an amateur actor who was not a party figure. The rest of the film was half-reconstruction of a party meeting and half-improvisation, although it does not prevent the film from making a completely authentic impression. Later Kieślowski turned the film script into a play, but it was much less suited for theatre.

Curriculum Vitae revealed new structural and stylistic capacities of documentary film, which was followed up in a slightly different way in two philosophical films: Seven Women of Different Agesand Talking Heads. His growing interest in philosophical conceptualism was fully realized in his next fiction films: Blind Chance, The Double Life of Veronique, Three Colours, and in the Dekalog series.

But Kieślowski’s faith in documentary cinema was shaken by two experiences. In 1971, in the wake of the tragic events of December 1970 on the Baltic coast (the December workers’ riot in Poland. Ed.), when the Communist Party dispersed workers’ protests with bullets, Krzysztof Kieślowski and Tomasz Zygadło believed that a change in the party rule is a significant political transformation which they will be able to document honestly and without censorship interference. That’s what they were told. But it was naive to believe this: the management of the TV station which the filmmakers worked with edited their feature documentary so much that it was unrecognizable. This rid Kieślowski of the ambition of creating openly political documentary cinema.

Another turning point which eventually led Kieślowski to turn away from documentary filmmaking was From a Night Porter's Point of View. His protagonist, a member of civilian militia and a night guard, was an unpleasant, primitive person with a fascist mentality. In a way, he served as a satirical metaphor of the contemporary authorities, and his catchphrase, “my hobby is control,” came to be commonly used. The film got great reviews, won awards, people were laughing at the protagonist in cinemas, but Krzysztof felt horrible.

He felt like he used his protagonist, that he manipulated. And although the character himself was pleased with his image, this moral discomfort affected Krzysztof and made him practically give up documentary filmmaking in favor of fiction. Which then brought him world fame.

Notes

[1] This was where a group of younger filmmakers with similar artistic and political views formed around Bohdan Kosiński. In addition to the apparent leader Kieślowski, the group included Tomasz Zygadło, Andrzej Titkow, Marcel Łoziński, Paweł Kędzierski, the cinematographers Witold Stok and Jacek Petrycki.

_____________

The films from the Krzysztof Kieślowski: a documentary biography programme will be screened at the DOCUSPACE online cinema.

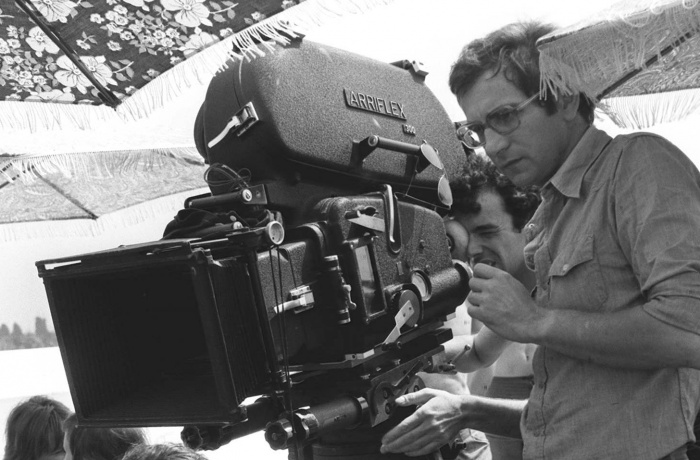

Header photo: Wiadomosci.onet.pl.

Stills from From the City of Łódź, The Factory, X-Ray.

Krzysztof Kieślowski: a documentary biography programme is supported by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland, the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and the Polish Institute.

The 18 Docudays UA is supported by the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine, the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation and the State Film Agency of Ukraine.