Wintopia is a film by the Canadian director Mira Burt-Wintonick. Mira is the daughter of Peter Wintonick, a well-known documentary filmmaker who died of cancer in 2013, aged 60. The elder Wintonick started by editing an election campaign video for Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. In the early 1980s, he created several films about American bohemia, including profiles of Allen Ginsberg and Charles Bukowski (these fragments were included into Wintopia). Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, he was involved in directing and producing. His most famous work is Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media.

Towards the end of his life, Peter Wintonick was drawn to the phenomenon of utopia – the mythical land of happiness. He wanted to make a movie with this title but wasn’t able to finish it. Mira Burt-Wintonick gathered the materials shot by her father, added family chronicles, numerous emails and postcards sent to her by ‘father Pete’. It turned out as a diary film – very sweet, calm and quite consoling. Natalya Serebriakova talked with Mira Burt-Wintonick about her film and her father.

The film begins with a wonderful quote from your father: “The glass is half full and half fool”. What do you think it means?

I like this quote because it’s a riddle similar to Zen koans. Here is my interpretation: this is an answer to an idea that being an optimist is unwise and naive. My father hints that seeing the glass as half-empty is foolish. This way, one can easily fall into the trap of pessimism and reject the power of hope.

How did the idea to finish Peter’s utopia emerge?

Before he died, my father wanted to make a movie about himself and his life’s work. He had been working on the utopia film for years, but in the end had to give it up to make other films. No one has seen the footage of his utopia, but the search for it seemed to form a metaphor for my father’s artistic life. Then I decided to gather the tapes and portray him and our relationship through this unfinished film.

What were your first memories of your father related to his work?

I remember when I was six, he asked me to walk up on stage for his film Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media. Back then I didn’t know or care about who Noam Chomsky was. My father simply bribed me with a cookie. Of course, now I consider the film a masterpiece. I also remember receiving postcards from places far away when he was travelling. I thought he had a cooler job than the fathers of my school friends, although I missed him while he was gone.

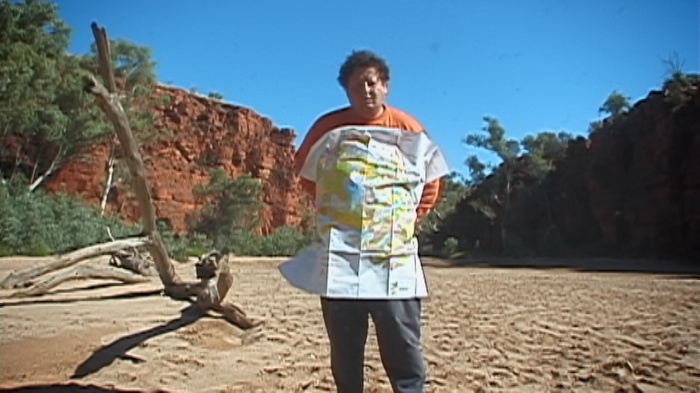

A still from Wintopia

Did you see all his films? What is your favourite and why?

I saw all the films he directed. But I don’t think I have seen every film he worked on or had influence on because there are literally thousands of them. Manufacturing Consent is a masterpiece which is still relevant in the perspective of shaping public opinion through mass media. Seeing is Believing is another acute film about how access to portable cameras (and nowadays, the omnipresent smartphones) allowed citizens and activists to document injustice and human rights violations around the world.

Can you tell more about his unfinished project Utopia? What did he mean by this word?

The word ‘utopia’ means a perfect place that does not exist. I think my father was enchanted by this mystery of searching for and building a perfect world. He spent 15 years visiting eco-settlements, communes and cooperative industries, meeting people who were trying to create a microsociety where everything could be better for everyone, not just those in power. He thought that a film about utopia would encapsulate all the pictures of the possible worlds, and that imagining a better world is the first step towards its realization.

Are diary films your style?

I like personal documentary films. Making yourself vulnerable and opening your emotional experience to the audience is a very powerful and moving step. It allows people to empathise deeply with the story you are trying to tell.

What is your favourite diary film?

I like Sherman’s March by Ross McElwee for its humour and playfulness. It begins as a film about a Civil War general and turns into the most personal film about the director’s love life.

Your film turned out very warm and intimate. Clearly, you put a lot of love into it. How has it been received by the film critics and the audiences?

Wintopia was received with a lot of warmth. My film is a story of a father and a daughter, touching upon general topics of loss and grief. I think people value the fact that the emotions in the film are sincere, and it makes them reflect on their own lives and relationships.

Did your father want you to become a film director?

According to him, he was a documentary filmmaker because of the ‘vow of poverty’ all the documentary filmmakers have to take. He wanted me to become an architect or a musician. In the end, I think he would have been proud that I followed his steps.

What was the most difficult part of working on Wintopia?

The creative process, intertwined with grief for dad. It is useful in some way to have a project related to grief, but very bitter at the same time. I spent months and months sitting in a dark room, editing the film and watching the footage of my dead father. It took me two years to finish the film because I needed some distance and time to process my feelings before I could set out on a journey again.