This year’s retrospective program at DOCUDAYS UA is dedicated to the well-known Ukrainian documentary filmmaker and director of photography Oleksandr Koval. Mr. Koval passed away in autumn last year, leaving behind several dozen wonderful films. On 24, 25 and 27 March, in the Scene 6 space at the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre, the audience will have a chance to see a selection of iconic films which the master directed and photographed, in particular the short films Malanka’s Wedding, Oh Dear, These Guests Have Come to Me, Grandpa Ivan from the Village of Richky, The Silent Sector, the feature-length documentary Home. Native Land, and a short about Oleksandr Koval from the Unknown Films series created in the late 1990s by the Internews Ukraine International Media Centre.

Before the festival, we asked Stanislav Menzelevsky, the Dovzhenko Centre’s research and programming director, to talk to the director Serhiy Bukovsky and the writer and editor Viktoria Bondar about the works of Oleksandr Koval. Serhiy calls himself the master’s student, and Viktoria worked for a long time as the editor-in-chief of the UkrCineChronicles studio alongside Oleksandr Koval. During the retrospective, Viktoria and Serhiy will present Koval’s films to the audience.

To watch Soviet films and ‘understand’ their directors, it is important to realise that filmmaking is a collective process which depends on government support – to understand how the studio system worked (UkrCineChronicles in particular), how directors got the opportunity to make films, why these particular topics, whether it was always their own choice, and so on. Understanding the context can change our concept of a film artist considerably. The contemporary ‘free’ generation of filmmakers who are used to different production and funding models probably don’t know what a ‘topic plan’ is, and they often make films about whatever they wish.

Viktoria Bondar: I would edit this statement a bit. Filmmakers make ‘whatever they wish’ for their own money. In all the other cases, everything is dictated by the producer.

Serhiy Bukovsky: Or the rules of the State Film Agency.

I mean the popular concept that the repressive Soviet system oppressed cinema.

SB: …which existed in the grip of servitude.

Yes, and today we have freedom and democracy.

SB: And also a renaissance.

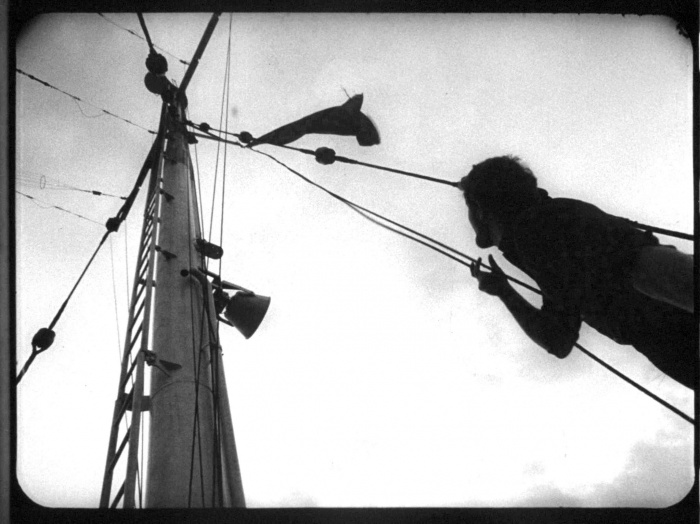

From the film The Silent Sector

The liberal model, the neutral market, the available equipment.

SB: I came to the studio when I was a college student and I started to work as an assistant for Oleksandr Koval. After graduation, it was impossible to get the opportunity to do your own directing work. First, you had to work as an assistant, then they trusted you with making a film journal or some kind of commission. And only then could you debut with a short for the mass screen. So I made my first feature-length film when I had already worked at the studio for three or four years. Let’s go back to Oleksandr’s generation. Koval and his colleagues did an incredible thing in their time, in the late 1970s and the early 1980s. They changed the type of protagonist on the documentary screen – from propaganda-style milkmaids and tractor operators to living people. Because the whole Soviet documentary cinema was ‘nailed’ to the floor with metal racks and heavy cameras, all the kolkhoz and industry workers looked about the same.

Let’s remember that in the West in the early 1960s, Robert Drew, the enterprising editor of Life magazine, was behind the so-called Direct Cinema. His specifications were used to design lightweight cameras and special sound recorders. Koval’s generation did the same thing here, but without specifications or government funding.

Our camera technology workshop made miracles under the leadership of its chief engineer Yukhym Fridman, a candidate of technical sciences, who was, by the way, the father of the producer Oleksandr Rodniansky. Back then, you couldn’t just buy a GoPro, put it on your head and go film a movie. It was Oleksandr’s generation who allowed us to change the look and the language of documentary film. A living protagonist was introduced, the cameramen started to film spontaneous, ‘accidental’ life. Oleksandr was both a director and a cameraman, ‘camerector,’ as we said back then. A chronicle cameraman was a respectable person; at the UkrCineChronicles he even earned 50 rubles more than the director. Oleksandr graduated from the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography, and his teacher was another ‘man with a camera,’ Roman Karmen.

From the film The Silent Sector

In general, Koval and his colleagues moved documentary filmmaking forward; they made it lively and interesting.

Another important factor was the film quotas. To create a 10-minute motion picture, you received a total of 50 minutes of film. And that was it. You had to concentrate, to prepare for your conversation with the protagonist, to understand beforehand what you were going to film. Today, everyone films dozens of hours, terabytes.

And edits for years.

SB: Exactly. And back then, everything was limited, and these restrictions had a terrible disciplinary effect. We thought about every shot and episode. The good films of those years are the films of a great image-making culture.

VB: And content-making culture.

Where did people learn this content- and image-making?

SB: The school of film photography at the Karpenko-Kary University was always among the best, it had good teachers. And, of course, the Gerasimov Institute. Oleksandr is from the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography, which was an institution where even the walls could teach you.

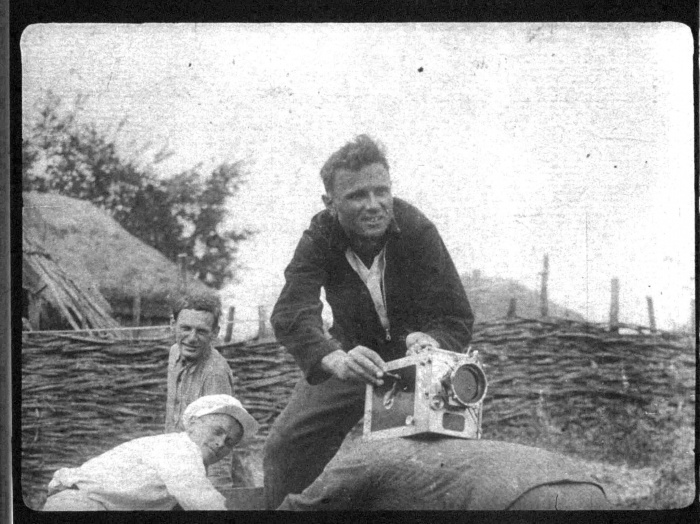

From the film Malanka’s Wedding

You have described the traditional career stages at the studio. Oleksandr Koval started his career as a lighting engineer...

VB: Or rather, as an assistant.

SB: Oleksandr was a chatterbox, in a good sense. He could tell a story that would make you roll on the floor. He was born on 7 May 1945, almost on Victory Day. He had never seen his father, who died in the war. But he worshipped his mother. Malanka’s Wedding was, among other things, about his mother Nadia. Sasha made films about the things which he knew, which he understood. In general, he understood village life and spoke the same language as these people.

When he was 16, Oleksandr left for the big life: he went to the city. And he became an assistant in a studio to a good teacher, the wonderful cameraman Eduard Timlin. Later, Koval was sent to the Gerasimov Institute, and he returned to the studio as a qualified director and operator with a degree.

VB: The Soviet production system was very similar to the contemporary Ukrainian system. I was the studio’s editor-in-chief during perestroika, and I am happy that I had something to do with many unique works. There was always a topic plan, approved by the State Film Agency, just like now. And directors with experience could choose from those topics, to one extent or another. Scripts were written in a similar manner. But the better directors never stuck to the scripts.

For example, in Oleksandr’s films Malanka’s Wedding and Grandpa Ivan from the Village of Richky, there are the required attributes of the era, such as a conversation with the head of the kolkhoz. But the contemporary professional audience must see something else behind the official cliche, such as character development. You need to know how to read other meanings.

There were cases when films were made so artfully that they never reached the audience. The State Cinema Agency watched them and said ‘No’ for ideological reasons.

SB: Soviet documentary filmmaking was directly linked to the ideological demand. So a good film was an allegory. Oleksandr used to say that for a film to pass, you needed to make an ‘English sandwich.’ We all listened to him with our mouths open. “To put a layer of crap, you need to put a layer of jam before and after it.” You need to retouch everything very well, so that nobody could notice anything.

VB: ‘Nobody’ in the administration. But the audience were supposed to see it.

From the film Oh Dear, These Guests Have Come to Me

And did the administration have the watching skills?

SB: They really did. There were two types of censorship. The ideological censorship, to make sure that nothing anti-Soviet comes out, and the military censorship. Someone came and checked: this is a military part, this is the Paton Bridge. This part existed before, but it became stricter after the ‘Thaw,’ in the times of Brezhnev and Shcherbytsky. As Oleksandr used to say, culture is a window between two cults.

VB: I remember something from my past in television. We once invited a filmmaker to our TV studio. And suddenly the recording stopped, the head of the committee called and said, “Can you see what’s happening in your studio?” Nothing seemed to be happening. But when we looked into it, it turned out that the filmmaker put on a yellow shirt with a light blue tie.

SB: When Ukraine became independent and we became free, Oleksandr’s generation was not prepared for everything to be allowed, so they were lost. They were used to speaking a different, metaphorical language. Many of them stopped making films.

VB: At first, everyone made their statements. Oleksandr made the film Home. Native Land, a personal, sand and honest statement about himself. If you watch the film carefully, you can notice the bitterness of a person who was forced to hide himself.

SB: The film is also about land and the tragedy of the villagers.

VB: Oleksandr was a person who had one foot was in the village and the other in the city. He never became a completely urban person.

SB: He lived on the train between the village of Zherdova and Kyiv.

VB: And then the studio started to die. Serhiy and I left it in 1993.

SB: The Soviet Union had about 40 such studios, but the government didn’t need them anymore.

VB: Nobody wanted to pay money for someone to criticise them.

SB: Because these studios were founded as parts of a powerful propaganda machine, UkrCineChronicles among them.

VB: Mainly.

SB: It was nicknamed ‘parquet film.’ Oleksandr and other people like him, such as the director and cameraman Murat Mamedov, tried to dance on this parquet and tell the truth.

VB: When the ‘curtain’ fell, documentaries were in the highest demand. A selection of the 22 best Soviet documentaries was demonstrated all over the world. Four of them were Ukrainian.

I asked about the topic plan for a reason, because if you look at Koval’s filmography, you see a wide range of topics. Was he himself able to construct that ‘sandwich’? Which of his films do you consider the best?

SB: All the best films will be screened at Docudays UA. And we contributed to that selection. You cannot make art every day. They made many films, it was a real factory. But some ‘madmen’ wanted to make art, and they managed to do it, with great effort, sometimes.

VB: As for specific titles, Malanka’s Wedding, of course. This film revealed new horizons. Oh Dear, These Guests Have Come to Me by Pavlo Fareniuk is also worth mentioning. Oleksandr was the cameraman for this film. It’s a story of a woman who survived the Holodomor. When the film was made, in 1989, she was living in a dugout house. It was one of the first films about the Holodomor.

SB: It was a taboo. This topic only started to be discussed during perestroika.

VB: And this amazing film was just forgotten, while actually it should be recorded in the history of cinema in the biggest font. That was the first time when Khvyliovyi’s words were recited in a film.

And, of course, Home. Native Land. This film was wonderfully made and brilliantly constructed from the dramatic perspective.

SB: Films age very quickly. The era passes, and the films age together with that country and that time. But some of Oleksandr’s films just get better every year.

From the film Oh Dear, These Guests Have Come to Me

It was quite predictable that the topic of the Holodomor would be taboo. But I want to recall a rather strange incident with the film Discover Yourself by Rolan Serhiyenko, where Koval was the director of photography. Skovoroda was successfully integrated in the Soviet cultural canon, he was turned into a warrior for the ideals of the October Revolution. Ivan Kavaleridze made a feature film about him in 1959, and in 1977 a monument to Skovoroda was installed, also designed by Kavaleridze. But at the same time, in 1972, Serhiyenko’s film about this monument was banned!

VB: Because in that film, Skovoroda didn’t act as a monument, he acted as a living person with living thoughts, as the actual famous philosopher, without the Soviet polish.

SB: In the scene where the monument is cast, it is hit on the head with a sledgehammer. It’s a very direct hint. It was recognized, ‘read.’

Other than seditious philosophical thought, what else was banned? Oleksandr once confessed that he wasn’t allowed to make films about the country or about the villagers.

SB: The truth about the land and the fate of the villagers. Country people lived without IDs for a very long time, they were basically slaves to the Soviet system. Oleksandr’s dream was that his students should move to Zherdova and film a true chronicle of village life.

VB: You could only sing praise to the village: a million pounds of bread have been collected, millions of litres of milk have been milked… But the real problems were left outside the frame.

SB: Many things were banned. One of the loyal topics where you could at least say something was the war. Next to the heroic deeds of the Soviet people, you could show human grief — as in the case of Malanka’s Wedding.

To conclude the conversation, I want to ask, how were documentary films watched in Koval’s era, and who were his audience? When were the films from our retrospective last shown on a big screen?

VB: I cannot answer the last question. Most likely, they were screened at various anniversaries in the Blue Hall of the House of Cinema. They don’t show such films on TV, maybe only after midnight. The Orbita cinema in Kyiv used to exclusively show non-fiction films, and there were lines outside to watch them. For example, for the films by Felix Sobolev.

SB: When a film by Sobolev was screened in the Russia Cinema in Moscow, there was even some commotion, the mounted police were sent to deal with it.

VB: Documentary films were also screened before feature films at so-called ‘extended screenings.’ Also, in various film clubs, for example, at the Subway Construction Company or at the Railway Workers Club. And on TV. There were a number of TV shows that popularised documentary filmmaking: Resonance, Filming. Our film studio received bags of letters with reviews and suggestions. It was a version of contemporary audience ranking. Documentary films did have their own audience. Just like Docudays has its audience today.

Conversation by Stanislav Menzelevsky