This year’s DOCU/BEST collection of the world-renowned documentary films includes Bridges of Time, which is the result of a cooperation between Latvian filmmaker Kristīne Briede and the Lithuanian master of poetic cinema Audrius Stonys. Their documentary film about the directors of the 1960s ‘Baltic new wave’ returns frames from films about humanity and freedom during the totalitarian era to the big screen. The world premiere of Bridges of Time took place at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. Audrius Stonys, one of the film’s creators, will attend the film’s screening at DOCUDAYS UA in Kyiv to present it to the audience personally. Film critic Natalia Serebriakova contacted Audrius Stonys and discussed with him the process of the film’s creation, the ‘Baltic new wave’, the nature of documentary cinema, and the possibility of turning a film into a time machine.

Your film Bridges of Time deals with the ‘Baltic new wave’ generation of documentary filmmakers. What interested you in this theme?

One can say that, instead of me choosing the theme, the theme chose me. According to the idea from the Lithuanian filmmaker Kristīne Briede, I was supposed to be a character in this film, a certain link between the filmmakers from the 1960s generation who were my teachers and friends, and the new generation whom I currently teach at the academy. However, I started to move from the role of character to the role of director.

Leaving the technical details aside, this period of Baltic cinema means a lot to me. Henrikas Šablevičius, Herz Frank, Robertas Verba – all of these directors are dear and close to me. I knew them personally and considered them my teachers. Working with their heritage was a valuable act for me.

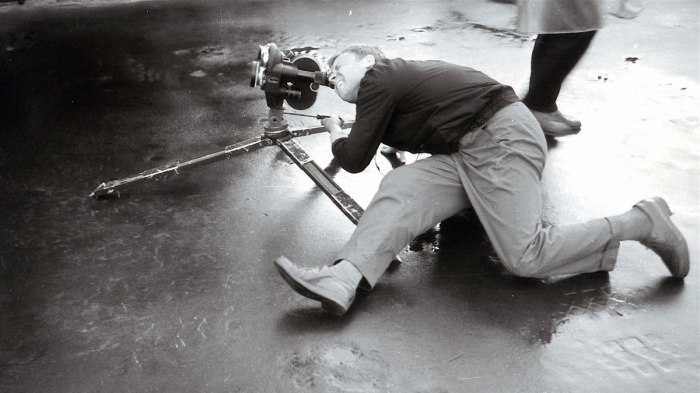

From the film Bridges of Time

This is a montage film, which includes many pieces from the films of the directors you are talking about. How did you work with the archive material? Did you plan its proportion to the amount of your own footage?

I didn’t think so much about it. I simply shared the frames I liked, without counting the percentage of the archive material. I did not set any proportions at all. Some directors appear in the film more than others, but this is a mere coincidence. I wanted to express myself through their frames and through my own touches to these frames. This is why I never reflected on whether this would result in a montage film or a classic documentary. I just went from film to film, looking for the landscapes that would open the doors into the past.

Why do you open your narrative with Herz Frank?

For me, the most important director is Henrikas Šablevičius. But it turned out that the episode about him is the shortest one in the film.

Herz Frank was a representative of poetic intuitive cinema. He is the only one of the 60s generation who articulated and generalised the crucial issues of the ‘Baltic new wave’. He published two books: The Book of Ptolemy and Turn Around at the Threshold. Frank came from Jewish culture, and he raised deep Biblical questions. To a certain extent, he became the mind and the voice of this period of Baltic cinema: other directors from this school were less outspoken, and Herz Frank delineates an important vertical.

Jonas Mekas, the well-known American filmmaker of Lithuanian origin was your teacher. Recently he passed away…

I can grasp this fact with a cool head – he lived a long life, after all. However, his soul remained so young that one could hardly believe the day of his death would eventually come. It seemed that he would be like this forever. It is very sad that the world has lost such a living soul, a real artist, light as a feather flying around the world. This is a huge loss for humanity. To me personally, he was one of the key figures I’ve met during my artistic life. I often recall him – I miss his smile, his easy attitude towards what we’re doing. He had this unique combination of depth and airiness.

How did you become his student?

In the 1990s, Mekas invited ten Latvian students who were studying in Tbilisi. This dozen included me and Arūnas Matelis. We arrived in New York and spent a whole month at his cinematheque, watching films from dusk until dawn. We used to talk, grabbed some beer or tequila, and then got back to watching films. This month raced by, and it influenced all of us. Mekas opened up entirely new worlds to us. After the Soviet ‘iron curtain’, all of this was a shock. For Mekas, cinema was a game as serious as life itself.

What did you learn from Mekas from the technical point of view? For instance, you never use the rapid montage that he preferred…

Actually, it never occurred to Mekas to teach us anything. He simply shared his own world with us. His cinematheque was a whole universe. Mekas showed us films, and perhaps the most important discovery was that cinema could be very different. He used to say that one cannot draw a line between cinema and non-cinema, between what was allowed and not allowed. For him, any rules were superfluous – he perceived cinema as a conversation. During a conversation, people do not make each other ‘express themselves in a certain way’. Thus Mekas taught us freedom, giving us an understanding of the world’s beauty and a sense of space where one can look for oneself and find oneself.

Bridges of Time is a film about directors. Why did you personally decide to become a documentary filmmaker?

I come from a family of actors, so I was initially planning to commit my life to theatre. However, while studying at the conservatory, I met Henrikas Šablevičius. He was such a charismatic person, who utterly fascinated me with his stories about documentary cinema. When I started to look into it, I couldn’t stop. I was no longer interested in inventing something – all I had to do was to discover and feel surprised. The world unfolding in front of you is part of documentary cinema. You just contemplate and try to capture this wonder. The world is so interesting that there is neither time nor point in fantasising.

From the film Bridges of Time

What is more important to you about documentaries: the plot or the visual aspect?

The image can speak as well! It says deeper and more interesting things than hundreds of words. I think that every landscape contains a narrative. One has to trust the image, allowing it to reveal itself. There are no empty images – each of them comprises an inner story. The question is how you unfold it. Sometimes the words that the filmmaker comes up with are superfluous.

Do you, as a documentary filmmaker, consider cinema a time machine?

Indeed, this is one of the most interesting tasks of documentaries. Cinema was born from the desire to stop time and to preserve it. Jonas Mekas used to say, “I’ve lost too much in my life to lose these fleeting moments as well.” He began capturing time, his friends, landscapes and so on, in order to save all of them from oblivion and disappearance. Mekas was the poet of time. Previously, I used to think that I was interested in the issue of loneliness, but now I think that time is above all. What time does to us and to the world, how not to lose the things that are passing by…

Has this occurred to you with aging?

Correct. I’ve begun to feel the current of time. I’ve begun losing people. I’ve lost Šablevičius, Mekas... Audrius Kemežys, the cinematographer who shot my previous film Woman and the Glacier, has also passed away… Losing the people dear to you, you begin to wonder about the flow of time and the transience of human life. You turn the mirror to yourself and think: what is going on with you? The matter of time is the most important.

How did you work with the elements of the Soviet past in the archival materials while creating Bridges of Time?

In my view, the Soviet Union simply did not exist for the directors of the ‘Baltic new wave’. They were inherently free. They were among those who preserved their liberty during the times of totalitarianism. At the same time, there are still people in independent Lithuania who keep living as if they were still in the Soviet times.

I wanted to get around this issue in the film, because this is a filthy system, and I do not want to give it any significance. My opinion is that the filmmakers of the Baltic poetic documentaries were higher, deeper, and stronger than this system.

Last year’s Docudays UA featured the retrospective of another Lithuanian director, Arūnas Matelis. You have created two films together. Is there something that unites your generations of filmmakers?

Arūnas Matelis is a close friend of mine. We studied and made films together. Sometimes, people mix us up: I receive his accreditations, and he receives mine. I consider him my brother. We are not part of Herz Frank’s generation. We were the first creative generation of Independence. Our graduation works were created just before Independence. The old system was destroyed, and the new one was not yet created, so we had to make our films on these ruins.

Interview by Natalia Serebriakova