Film critic Ihor Hrabovych tells about the DOCU/UKRAINE, the first full-length competition programme in the festival’s history.

The DOCU/UKRAINE full-length competition programme for the national cinema is a sensational and unprecedented event in the festival’s history. It proves the maturity of the festival and of Ukrainian cinema, which is evident not only from the quantity and the themes of the movies, but also from the geography of the participants in the cinematic process, which is not confined to Ukraine alone.

This year’s national competition can be divided into two parts: half of the films were made by Ukraine-based filmmakers, who mostly operate in the national context, while the other half were filmed by those directors whose lives and work have for some time been related to other countries, and whose perspective includes a broader, international context. However, the depiction of contemporary Ukraine in their films is of special interest.

The film Enticing, Sugary, Boundless or Songs and Dances about Death by Tania Khodakivska and Oleksandr Stekolenko is planetary in its scope. This movie brings together various cultures, countries, and people. It depicts the USA, Italy, Ukraine, and Georgia, and the characters include famous artists as well as ordinary people.

Enticing, Sugary, Boundless or Songs and Dances about Death by Tania Khodakivska and Oleksandr Stekolenko

The universality of the questions and challenges which the characters face makes them very similar, perhaps except for the regional differences in their tempers. The structure of the film is symphonic. The locations switch from country to country, the themes rhyme, contrasts are blurred, and the similarities of human destinies come to the foreground.

The ‘Sugary’ episode of the film is dedicated to Ukraine, even though the life it depicts can hardly be named sweet. It is not about social processes, politics, or other phenomena; the most important thing is the existential horizon that the individual is able to perceive. The stoicism of the natives of the Ukrainian Carpathians, their kindness and humour, and the artistic experiments of the ballet dancers from Kyiv, who are ready for everyday challenges, seem to be unimportant in a global sense, but that is precisely what life is about. Every moment of existence matters, because nothing will happen after death, as the characters say.

Death in the film is equal to a montage, where the key roles belong to unexpected shifts, weird associations, and the twisted final, the meaning of which is revealed subsequently. In this sense, the movie Enticing, Sugary, Boundless or Songs and Dances about Death is illustrative of the national competition programme, which comprises many montage films and stories without a clear ending.

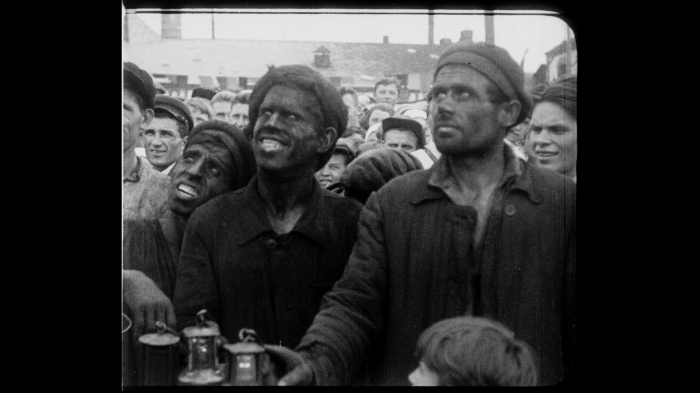

The second approach to Ukraine is also planetary. The film by Igor Minaev, who is originally from Odesa but lives and works in France, is named The Cacophony of the Donbas and starts with the landscapes of the Donbas as seen from above. This landscape is compared to an abstract painting and an extinct star. It seems that humans simply cannot inhabit this land, which is entirely mythical, shrouded with legends and mysteries. We have to rediscover it. But first, we have to recall its recent history, to see how it was formed and what it was made from. In this way Minaev makes a deconstruction of the Donbas.

The Cacophony of the Donbas by Igor Minaev

He begins with the cinema and the Soviet cinematic aesthetic which created an image of the Donbas that was far from reality. This is equally true for the movie avant-garde, represented in the film by Dziga Vertov’s Symphony of the Donbass, for the average socialist realism of Soviet films about the working class, and for the news footage, which concealed reality and sometimes even created a parallel one. This approach may seem strange, as one might expect the analysis to be based on economic, sociological, political or demographic criteria. However, the filmmaker chooses those of aesthetics, and this is quite justified because in this case aesthetics is nothing else than a protective screen which has been used as a separator from reality.

The reality breaks onto the screen in the documentary shots of the 1989 miners’ strike, when we first see the real miners and their problems, and then continues to the documentary footage of the war in the Donbas. The paradox is that the new reality finds new aesthetic forms, since it cannot do without aesthetics as well. This aesthetic is rather experimental, even excitable, on the edge of kitsch, and, instead of transmitting a gross social truth, it aesthetically transforms the reality, revealing its hidden meaning, something which can be interpreted as perverse.

The Cacophony of the Donbass is an experimental film, and the author resorts to some generalisations that sound apocalyptic. This position is understandable, because approaching earth from heaven is always painful.

In Dmytro Lavrinenko’s Whereufrom, instead of approaching the earth, we see the immersion under its surface – in the garbage, to be precise. The movie tells the life story of 45-year-old Yevhen, a janitor from Kharkiv, who lives between two worlds – Kharkiv and America. He visits America because his mother is residing there, while he himself lives in Kharkiv full-time. Kharkiv is his motherland and his whole life, and America remains an accidental passerby with whom he cannot establish contact.

Whereufrom by Dmytro Lavrinenko

The film consists of Yevhen’s video diaries that represent his subjective viewpoint, as well as footage shot by director Dmytro Lavrinenko, which brings a seemingly objective angle to the story. The dialogue between these voices makes the film very convincing, material, daring, and even shocking in some of the episodes. The shock here lies in the behaviour of Yevhen, who is looking for his dream woman, and collecting artifacts from Soviet times. The latter appear much more often than the former. The events of the film take place between 2011 and 2017. Many events take place in Ukraine during this time, including Euro 2012 and the Revolution of Dignity, and Yevhen participates in all of them, leading us through the circles of his personal hell, similar to Virgil.

Another collection of the films in this competition is created by Ukrainian filmmakers that regard Ukraine without any additional international perspectives. This is not an easy task nowadays, as the events in the homeland are quite dramatic, and the degree of drama is constantly rising. In this situation, telling a consistent story is rather difficult. The successful results become even more interesting in this regard.

The First Company by Yaroslav Pilunskyi, Yulia Shashkova and Yuriy Grizunov, is structurally complete. It features a narration about the lives and fates of some of the activists of the Revolution of Dignity who have created the First Company for Self-Defence at the Maidan, took part in all of the events, and, subsequently, went to war.

The First Company by Yaroslav Pilunskyi, Yulia Shashkova and Yuriy Grizunov

This story is important primarily because it is about the choice and the creation of one’s personal biography. This film is unprecedented in Ukrainian cinema, because the biographies here made an impact on the circumstances, and it was hard for someone to change tack, to overcome the inertia of social processes and one’s own life.

The First Company tells about people who have changed tack. This film is a summary of many other similar movies that have appeared in our country during recent years. All of them tell about human choices and their price.

However, The First Company presents the story in an unusual, even paradoxical way. It unfolds nonlinearly, much like the life of Charles Foster Kane, and the flashbacks in the film look almost epic and symbolic. This is a classical story about the formation of a cultural hero (or in this case, a group of people), who embarks on a perilous journey, overcomes obstacles, and finds a treasure in the end. What we have here is probably the first example of the newest national mythology.

Almost 10,000 Voters by Uliana Osovska also tells the story of the painful birth of this new world. The film concerns Illintsi, a small town in the Vinnytsia region, which lives through all the newest processes, including the Revolution of Dignity and the war in the east of Ukraine. The main issue, however, is not living through this, but changing one’s own life. This will not be an easy task.

Almost 10,000 Voters by Uliana Osovska

The mayoral election is coming soon in Illintsi. There are several candidates for this position, and the first violin is played by the former, pre-revolutionary rulers. They are opposed to the hero of the new times – an activist and volunteer, whose best features were revealed in the course of the Revolution of Dignity. Will he change the situation in Illintsi, and will the local community support him?

The film touches upon the acute issues of social responsibility, of grass-roots initiatives, and ultimately, the readiness of so-called ordinary people to make radical changes in their own lives. In this sense, the story is far from complete – the results of this process are very hard to predict. The key features of the film are the texture, the details of ordinary provincial life, even some grotesquery in the depiction of the governors. However, the ordinary people are in the foreground, trying to take care of themselves, to overcome fears and inertia. The women in the film are noticeably more active and courageous, which is indicative considering the global trends towards betting on ‘girl power’.

This is the main theme of Masha Kondakova’s Woman in War, which portrays a number of women combatants. As in The First Company, the narration here is non-linear, the locations shift frequently, and the focus passes from one character to another, creating a stereoscopic effect. This story is also about the choice that has to be made every day about the search for one’s destiny, one’s place in war and in peace, and about love.

Woman in War by Masha Kondakova

Contrary to similar films about women at war, this film does not have a specific issue, for instance, the rights of servicewomen or the traumas they experience. War here is merely a part of life, a horrid and frightening part which is no greater than life itself.

Life cannot be confined to war, but it cannot do without it either. This point is perhaps most important for all of us. The film Woman in War, like many other Ukrainian films about our recent history, removes our common fears of our own choices and our own fates. They cannot be sugar-sweet due to the circumstances, but they are still completely ours, and we can still deal with them.

These recent Ukrainian films, while depicting the dramatic events witnessed by our country and all of us, thrive to become something more than movies. They offer a feeling of our shared destiny, our common route, our common struggle, and in the end, our common victory.

Text: Ihor Hrabovych

Header photo: The First Company by Yaroslav Pilunskyi, Yulia Shashkova and Yuriy Grizunov