The most famous expert on documentaries has never even touched a film camera. Instead, Tue Steen Muller from Denmark knows how documentaries change the world.

In 20 years Tue Steen Muller has been a commissioning editor, a distributor, and a film festival manager at the Danish Film Academy. He was head of the European Documentary Network, and selected films and worked for film festivals like DOCSBarcelona, Magnificent7 and DOK Leipzig. Now Tue teaches and consults film directors in various European film schools, and most importantly, he is a renowned expert on modern Eastern European documentaries. He writes his observations in a blog which has helped some little-known filmmakers to find a wide audience.

For the Docudays UA film festival Tue Steen Muller put together a special program "High Five from Denmark" where he combined the best Danish films of different years to represent the evolution of documentary filmmaking in his country: from Jørgen Leth, the teacher of Lars von Trier, to the young directors who practice selfie-films.

Tue Steen Muller on Docudays UA - 2013

Actually, before our conversation, I wanted to ask you write a letter to a Ukrainian documentary filmmaker, an imaginary one. I wonder, how would you start such a letter?

Dear friends, I’m happy that you want to make documentaries. Remember that documentaries should be made out of a necessity from within you, it should mean something for you. Please don’t make something just for the sake of making something. When you start filming you should have what you want to do in your head. Otherwise the film will hit you like a boomerang. Join the club! Remember, if you’re making documentaries you will never be rich, you will never be famous, you will not hit the headlines, but you will have a very good life and you will be doing something which is very important to yourself and also to the people.

I think your blog filmkommentaren also resembles letters about documentary films. But why did you never start to make films, never take a camera in your hands?

I entered another door. When I started in film, I started as a critic. I wrote reviews for Danish film magazines and newspapers. Then I was invited to come and work at the Danish Film Board, when I was for 20 years, actually. That’s where I got my documentary injection, so to say. As they say in Italian, «‘con amore’». So I was never tempted to try to make films myself. On the other hand, during many of these 20 years I’ve been one of the so-called decision makers, meaning that I’ve been deciding who should get money to make films. In Danish terms we call it a film consultant, in international terms you call it a commissioning editor, but it’s the same thing – I’ve spent many hours in the editing room. So in a way I’ve been part of the making of films in many cases.

Tue Steen Muller on Docudays UA - 2013 (Docu/Class)

Could documentary films change something today? What can they give to viewers, to the people who are tired of TV and everyday hustle?

I think that documentaries can change something in the minds of the viewers. And I believe documentary films can transform a country. Could documentaries change something in Ukraine particularly? Only you can answer this question.

I’ll give you an example. There was a Danish film some years ago, called Armadillo, it is about young Danish soldiers going to Afghanistan, taking part in the battle against the Taliban. At that point we had never seen anything in Denmark about what Danish soldiers were doing over there. So it was a little bit of a fiction. But this film was very concrete, we saw that we were sending young soldiers over there, and they don’t really know what the war is. For them it’s a kind of a game. One of them was actually saying that it’s like going to a football game. He said that before coming over there. And the reality was of course totally different. This film was shown in Danish cinemas, and it had over one million viewers, all the members of the parliament were invited to see the film, there was a lot of press, etc. I think that it was a part of changing the perception of the Danish population towards our involvement in the Afghan war.

About the documentary movies in the special program on Docudays UA from you... What do they represent in the context of Denmark?

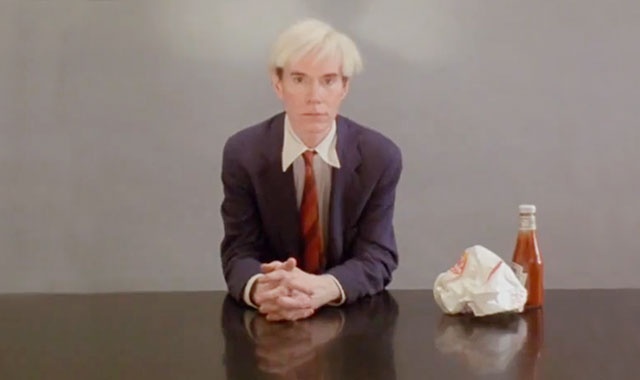

First of all, it includes films by Jørgen Leth. He is one of the big names in Danish documentaries. So these two films by him– one is called 66 Scenes from America and the other one is called Motion Picture – these two are examples of his experimenting with form. 66 Scenes from America is very much like a collection of photographs, it has a lot to do with pop art. The director is just staging people in different situations in the American landscape. In 1982 it was a big breakthrough, and the film has been a huge inspiration for newer generations of filmmakers. And Motion Picture is a playful examination of what it means to play tennis. I chose this film because it gives me an opportunity to say something about the Jørgen Leth who is a sports fanatic. Especially he enjoys bicycle racing.

66 Scenes from America

I also chose Jon Bang Carlsen’s It’s Now or Never because of its aesthetic. It’s about a bachelor in Ireland who is looking for a woman. The film is a mix of documentary and fiction. Today everybody is talking about hybrid films, but he had already done that way back in 1996.

A Family is a first-person film. Sami Saif, a young filmmaker, is looking for his father. It’s a kind of film which we did not have in Denmark before, sort of a selfie-documentary. His girlfriend at that time is behind the camera. She was also having a dialogue with him and triggering the action.

The Monastery was also a breakthrough, because the director did everything herself: she’s behind the camera, she’s helping her character who talks to her. Nobody thought that a film would come out of it. For seven years a young female director with a small camera was filming an old man whose big wish was to turn a ruined castle in Denmark into an Orthodox monastery. He goes to a patriarch in Moscow and gets permission. The film was a huge success and won prizes everywhere.

The Monastery

Would you say that this kind of overly intimate film is now trending in documentary filmmaking? Generally, how would you describe modern film language?

Let me give you an example of what we are going to see here in Belgrade at the Magnificent 7 Film Festival (we were talking with Tue Steen Muller while he was visiting a documentary film festival in Belgrade – editor). The film Our Last Tango from Buenos Aires is an intimate love story. It’s about these two old dancers. They were dancing together for over 40 years, but she feels betrayed when he suddenly finds a younger partner… Then we have a social documentary, Mallory. It is about a homeless woman, whom the director Helena Třeštíková filmed for over 13 years. She has a child, but can’t be with it, because she’s living in a car. It is a great example of a beautiful, humanistic, social documentary. Both of these things are possible in documentaries.

Another thing is that 15 years ago you wouldn’t be able to achieve extra intimacy due to technical issues. Today a small camera allows one to do that. For instance, there is a film from a Belgian-Israeli director who has been filming in the bedroom of his 94-year-old mother. A long time ago the doctors told her, «You’re not going to live very long.» But she keeps on living. And he comes and she’s so full of life, and they are talking about life. So this is a super intimate film about mother and son, and the wisdom of an old woman, her look at life, etc. And then there is a film, one of many, which is about the European Union’s biggest problem of all now, namely the refugee problem; it is called Lampedusa in Winter. Lampedusa is an island where all the poor people from the Middle East and Africa are coming for a temporary shelter. But this film brings up a broader context: what do the people on this island do when all these refugees arrive?

Documentaries are always a mirror of what is happening in the world. The social problems, the bigger political problems, like the refugee problem today, are one trend. But outside of this ‘bigger’ world there is a ‘smaller,’ intimate world: you and me, love and life.

The protagonist of the film The Monastery, from the program you will present, says to the director: «Always expect the unexpected — it is a law. No matter how much you plan something, something unexpected always happens.» I think this is the most honest thing that can happen in a documentary – these sudden sparks of life that the director can catch. Would you say that this is a law for documentaries?

Of course. To the letter. In the beginning I shout out the following: «Surprise me! Tell me something that I did not expect. Tell me something that I didn’t know beforehand. Move me!» I still think that it’s more important with the heart than the brain. To be touched emotionally is extremely important.

Interview by Vika Khomenko