Every film festival is like a montage process. Combination of a huge amount of industrial events, screenings and film presentations gives us ability to see how film landscapes are formed nowadays, and what forms them.

Our coordinators Viktoria Leshchenko and Olga Birzul have recently come back from known European film forums - festivals in Jihlava and Leipzig, where they presented the new Ukrainian documentary catalogue. Read their travel notes in our blog.

***

Viktoria Leshchenko

November 2016, Jihlava

I always have montage transition, when I cross the border. You come to Boryspil, get on a plane and find yourself on another planet in a few hours. Your life consists of 3-euro coffee, lots of films, meetings and being deadly tired. For people like me, suffering from intersections and doubts, this is a treatment prescribed by God. If it wasn’t for documentary films, I couldn’t even imagine myself on a seventeen-hour bus journey from Kyiv to Jihlava.

I think the process of crossing gets deep into the body memory. Not only because the body gets numb, swollen and less flexible. The crossing is a part of collective body now. It’s not just drivers, stewardesses, passengers, boxes with cats in the back and lots of parcels in the luggage. It’s a collective body, as in carnival culture. Of course not everyone can blend in immediately. The collective doesn’t like cats at first - because of the smell; untill all the people with allergies aren’t relocated to the front seats. Then the unity comes in the middle of the night, in a three-hour line on Polish border (I found out later that this was actually pretty quick). All of this for a ritual sacrifice before merciless Polish border guards - we threw away all the sandwiches packed for the long journey. It seemed to last forever, with grey shadows of people and cars behind the window.

15 hours later we were at Brno bus station. The first impression was - as if we never left home. “The life like a flea market” - travel bags, towels with hundred-dollar bill prints and funeral wreaths for sale. Not a soul around. Later we found out it was a state holiday. But the life was hiding behind the empty landscape of that bus station. The local money-changer was waiting for Ukrainians right around the corner. For a few more crones he will make you an instant coffee and smile showing a golden tooth.

Czech Republic is covered in golden leaves all October and part of November. Blinding beauty dissolves in peaceful towns. After entering Jihlava you realize: not only the driver doesn’t understand you - he is not local himself. We miss our stop and get out somewhere on the side of the road. Ukrainian migrants come to help, as usually: “Hey, did you come here to work, too?” A strange thing, Jihlava too still has trolley buses.

Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival has a jubilee this year. It is twenty years old. It’s program director Marek Hovorka has always been the big love here. The legend says, he founded the festival when he was 16. He wanted to perform in FAMU with his friends, but couldn’t - so they decided to organize the festival. Seems like those times aren’t over - the person who made designs for the festival is one of those friends.

The festival in Ihlava is known as a festival with innovative design solutions

The whole festival is very simple, practical and full of it’s creators’ taste. “It’s expensive, but it’s worth it” - say the collegues about stylish, minimalistic containers in the center. One of them is the festival museum with various artefacts - from t-shirts to prizes and authographs of celebrities. The other is a two-store location with a hall for film industry events on the first floor and a caffee with an autumn terrace on the second. The whole space has an aquarium feel to it. Transparent walls integrate the event zone with the square, drawing attention of the passers-by to everything happening inside.

Temporary location for film festival industrial activities

All the workshops, discussions with experts, guest introductions and industry drinks took place here. On the closing day we occupied the presentation space with the presentation of our catalogue of Ukrainian documentary films. We were nervous. When the hall full of future and already-funs of Ukrainian documentaries got emptier, our Czech collegues opened a bottle of wine with us and gave us two packs of Pringles. Eating the chips, we went to look for the closing ceremony, but didn’t find it. It turned out it was tense. People in the hall have been waiting for it to begin for a long time, and when it started, it turned out it was taking place somewhere else, with a live stream in that hall. There’s a lot of that here, if you know what I mean. Trolling like this is a special trait of Jihlava’s atmosphere.

Presentation of the new catalog of Ukrainian documentary at the festival in Ihlava

***

Olga Birzul

Leipzig, November 2016

I know five things about Leipzig. It’s a city of music - from Sebastian Bach to Felix Mendelssohn; the first peaceful revolution took place here in 1989, and it started the mechanism that led to the fall of the Berlin wall; you can hear Russian quite often here - the wall has fallen, but the soviet people stayed; history is not forgotten here - there were several concentration camps around Leipzig in times of the Second World War. And the last, the International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film, the program of which includes Ukrainian directors not only when there is a revolution or a war going on in their country.

Urban space of power - Bach Monument and Church of St. Nicholas, where in 1989 was held peaceful protest against the communist regime of GDR

This year’s DOK Leipzig is also rich on films about our reality. I use the word “rich” because I thing it’s significant, when an international film forum speaks about Ukraine more than in the context of the “Russian Woodpecker” by Chad Gracia. Of course the country looks sad in most films. But we really live in a difficult time, and sharp eye of a documentalist reflects that with sergical precision. “People Who Came to Power” by Tomáš Rafa and Olexiy Radynski, “Rodnye” by Vitaliy Mansky, “Bring the Jews Home” by Eefje Blankevoort and Arnold van Bruggen, “Oleg's Choice” by Elena Volochine and James Keogh with different success tell the foreign viewer about Ukrainian reality. It was a little embarrassing to watch them on wide screen with foreigners. It’s not an inferiority complex, but rather a wish to get out of your own aquarium just for a couple of days and clean your lens to see other, equally important world problems. That’s why I watched a Ukrainian film only once. It was “The Leading Role” by Serhiy Bukovsky, presented in the international competition.

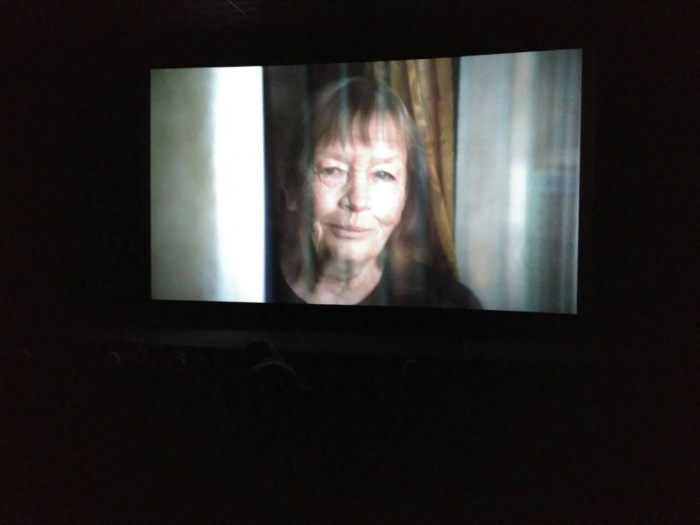

National problems in this film can only be seen in the view out of the window and in dominating tv-moves through which the main caracter remains faithful to her profession. Bukovsky turns the actress’s portrait into rather humorous reflections on skeletons in the closet, shadows of the past and chronical camera dependance. The main carachter, the director’s mother, was at the premiere. The moderator asks questions carefully, the author’s answers are discreet as well. The discussions here are quite short. Hot discussions usually take place at the coffee tables. One evening I asked Bukovsky if he had any doubts about being a father. “If I could come back in time, I would pay more attention to my children” - he said. I shrugged sadly. Is it even possible to build a ballanced relashionship between favourite work and family? Or it’s just a myth that profits modern psychologists and time-management books? I stop philosophising here. Much better news is that Docudays UA viewers have all the chances to see “The Leading Role” in March 2017 on wide screen.

Film screening "The main role" by Sergey Bukovsky

What our fectival lacks (but I hope we will have it, too) is a project like DOK Neuland. New technologies are undoubtedly entering cinema - it’s no news, and all the leadig film festivals are trying to keep up to date. Leipzig has been doing it for two years now. This time they have built an igloo-tent specially for interactive projects within documentary genre. Inside that tent you feel like Nanook who sees moving pictures on Flaherty’s tape for the first time. This project is more of an amusement ride for now, but the virtual reality glasses and interactive stories on tablets arouse true interest in the audience. By the way, it’s not easy to wait for your turn for a free sample. Virtual special effects allow you to understand the feeling of an autist in a country where this diagnosis is regarded as illness, or to see the world with the eyes of a person with visual disorders. Innovations inspire us to rethink common concepts and clichés.

Inside the igloo's DOKNeuland

Coming back to traditional film forms, the most destructive for clichés at DOK Leipzig for me was a film “A Hole in the Head” by slovakian director Robert Kirchhoff. In the center of the plot are Romani people who servived the nazi genocide. The main historical cynicism is that in 1982 Germany has officialy recognised nazi policies toward Roma and Sinti as genocide, but the monument dedicated to that events was built in Berlin only in 2012. The film takes place nowadays. There is a pig farm on Romani mass grave in one of the European towns nowadays. Good nonfictional films about Roma are rare indeed. This is one of them.

The streets of Leipzig during the festival

Rare things happen to us not only in the cinemas. For example, the first person we met in Leipzig was Jørgen Leth. This Danish film legend is mostly known because of his student, Lars von Trier, and their wonderful film “The Five Obstructions”. For two years his silhouette passed me by like a royal ship in Copenhagen, and I was only able to wave my hand in the crowd. This time it was late evening, and we were standing near Jørgen Leth with our suitcases, because we couldn’t figure out, how to open the hotel door. It was an old 18-century building with modern locks and a long instruction on how to open them. Like in the film, Leth overcomes this “obstruction”. We spent the rest of the night wondering, whether it was a dream.

I ran into Leth late in the evening for the second time. He was standing near our room confused, holding the keys.

- The lock again? - I asked.

- Worse. I don’t know how to get out of here.

- How did you get in?

- We were celebrating (in the next room - auth.) the festival winner. I forgot the laptop with some work in the room, but it seems like these keys don’t open all doors.

- Let me wait for you near the elevator. I will open our floor doors with my key. It can overcome the obstructions that weren’t in your film.

Main location of DOK Leipzig - City Museum of Art

We managed to tell Jørgen about Docudays UA and a little about Ukraine while we opened the doors. I understood deep inside, that this royal ship will pass me by again, but the hope dies last. On the next day we found out that international jury (Leth being one of them) has given the prize to Sergei Loznitsa for his film “Austerlitz” about Auschwitz concentration camp. The press pelease mentioned that Loznitsa was a «Ukrainian director». No coincidence, of course. Loznitsa was known in Leipzig for a long time (he received prizes for his first films here), and responsibility for concentration camps is well remembered here. This all makes sense.

Special thanks to Goethe Institute in Ukraine for their support of the journey.